|

|

[Last Modified: ] |

|

|

|

| [Cryptosporidium spp.] |

Microscopy

1)

Wet mounts:

Wet mount examination (with iodine) is used mainly for screening, and is especially useful

with specimens containing moderate to high numbers of oocysts. However, it should be

combined with a more sensitive confirmatory stain or assay. Fresh or concentrated fecal

specimens can be examined, using either conventional bright light, phase contrast or

differential interference contrast (or Nomarsky) microscopy.

|

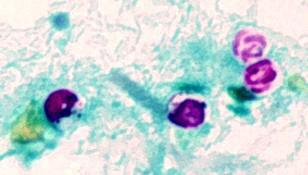

| A |

A: Oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum, in wet mount, seen with differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy. The oocysts are rounded, 4.2 to 5.4 µm in diameter. Sporozoites are visible inside the oocysts, indicating that sporulation has occurred. (In comparison, oocysts of Cyclospora cayetanensis, another important coccidian parasite of humans, are twice as large and upon excretion are not sporulated, i.e., do not contain sporocysts.)

2) Stained smears:

Traditional parasitology stains (e.g., Giemsa) are of limited value.

They do not differentiate between oocysts and similarly-sized fecal yeasts

(the main differential diagnosis of Cryptosporidium in microscopy)

and other debris. Modified acid-fast

staining technique is a simple and effective method: the oocysts stain

bright red against a background of blue-green fecal debris and yeasts.

The acid-fast staining technique has been modified and improved, including:

hot and cold modified acid-fast stains; incorporation of dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO); and incorporation of the detergent tergitol.

|

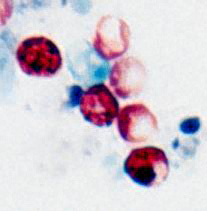

| B |

B: Oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum stained by the modified acid-fast method. Against a blue-green background, the oocysts stand out in a bright red stain. Sporozoites are visible inside the two oocysts to the right.

|

| C |

C: Oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum stained by the modified acid-fast method. This image shows that the staining can be variable. In particular, infections that are resolving can be accompanied by increasing numbers of non-acid-fast oocysts “ghosts.”

3) Immunofluorescence

microscopy for detection of oocysts:

This method offers increased sensitivity and specificity compared to staining

techniques. It has found widespread application in research and clinical laboratories as

well as for monitoring oocyst presence in environmental samples. The assays generally work

well with fresh or preserved stools (formalin, potassium dichromate), but some fixatives

can cause problems (e.g., MIF). Several commercial IFA products are presently available,

including MeriFluor™ Cryptosporidium/Giardia (Meridian Diagnostics

Inc., Cincinnati, OH, 45244, USA); Detect IF Cryptosporidium (Shield Diagnostics,

Ltd., Dundee DD1 1 SW, Scotland, UK); and Crypto IF Kit (TechLab, Blacksburg, VA, 24060,

USA). These assays exhibit broad reactivity with C. parvum and other Cryptosporidium

species, so they should be applicable to human and veterinary specimens.

|

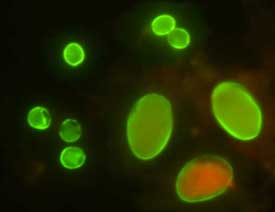

| D |

D: Oocysts of C. parvum (upper left) and cysts of Giardia intestinalis (lower right) labeled with immunofluorescent antibodies.

4) Several additional methods for microscopic detection of oocysts include:

- alternate bright-field stains (e.g., hot safranin-methylene blue stain, modified Kohn’s stain, modified Koster stain, aniline-carbol-methyl violet and tartrazine)

- negative stains

- fluorescent stains (including auramine O, auramine-rhodamine, auramine-carbol-fuchsin, acridine orange, mepacrine, and 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) and propidium iodide staining)

These exhibit potentially higher sensitivities but, like all nonspecific chemical staining methods, yield false-positives and may leave some oocysts unstained; these methods may be useful for screening samples, but identification should be confirmed with more specific assays (IFA, EIA).

|

| E |

E: Oocysts of Cryptosporidium parvum stained with the fluorescent stain auramine-rhodamine.

|

|||